From the self-sufficiency of old farmers to the Cyclades’ contemporary fava: how a tiny seed on an island of 150 permanent residents became a driver of identity, resilience and added value for the whole community

The ferry leaves Naxos behind and glides towards the Small Cyclades. Almost in the middle of nowhere, between Amorgos and Koufonisia, Schinoussa appears: nine square kilometres of land, three small settlements, fifteen beaches – all within walking distance.

“The island was built by people from Amorgos at the end of the 1800s,” Manolis Kovaïos tells me – the man who helped revive one of the most famous and delicious favas of the Aegean, Schinoussa fava. “The old folks came over on caiques boats, bringing animals, a few belongings, seeds and a lot of patience. The land was always the first capital: up until the 1970s, Schinoussa lived almost exclusively off its fields, its barley, a few vegetables ‘for the house’, and whatever the earth gave each family.”

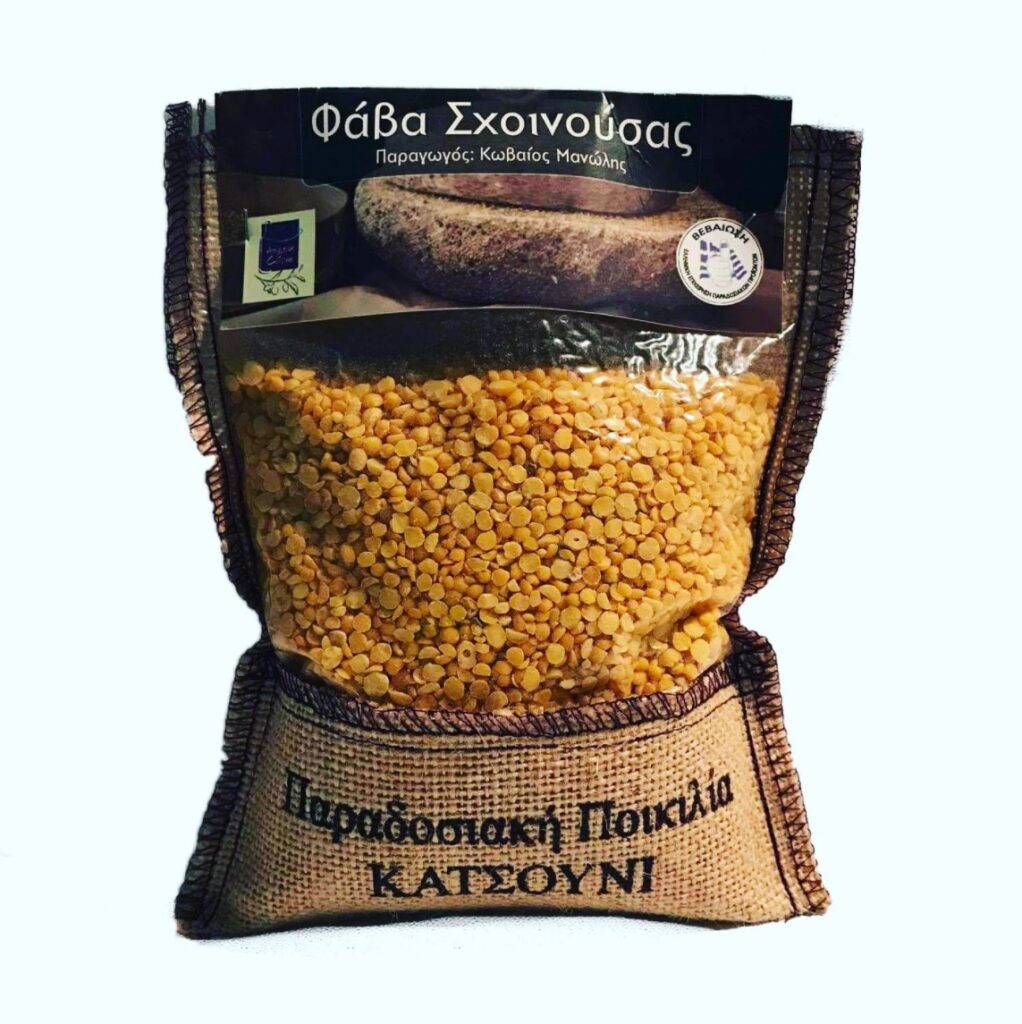

Within this small, austere farming universe, Schinoussa fava was born. A seed that arrived with the first settlers, probably a close relative of the variety they were already growing on Amorgos – the local pea known as katsouni (Pisum sativum). Each family cultivated it on a plot of one or two square kilometer, alongside barley which, up until the 1980s, was destined for Fix beer, the old Greek brewery.

It was never a market product; it was part of household self-sufficiency. Something kept in cloth sacks at home, giving life to a tradition and to a food that fed generations – and to a crop that passed from one generation to the next the way family secrets do.

From past to plate

Manolis belongs to that generation that still caught the sight of donkeys going round and round on the threshing floor. “I remember, as a kid, watching them circle, breaking the plants, and then we’d blow away the straw so the seeds would stay behind,” he tells me. Somewhere along the way, fava started to be abandoned: children left for Athens, tourism began to rise, the fields were left behind.

Until the moment he decided to do something that sounded almost crazy at the time: to take the seed back into his own hands. “I started with fifty kilos of my father’s seed in 2006,” he says. “In 2007 we did the first threshing in the field and I said: either we let it disappear, or we take it as far as it will go.”

“As far as it will go” turned out to be very far indeed. Schinoussa fava travelled to festivals, fairs and trade shows, won first prize at the Tselementes Festival in Sifnos, and when it appeared at EXPOTROF in 2014 many people spoke of the “other” fava of the Cyclades.

“Other” because it is made differently. The variety has nothing to do with the lathouri of Santorini; it is a different plant, a different texture, a different behaviour in the pot. “It’s like comparing mashed potatoes to carrot purée,” Manolis says – and that is exactly what it’s like. Schinoussa fava is softer, sweeter, paler. On the plate it has a bright, sunlit yellow colour and a flavour that recalls tender peas more than a classic legume.

And the most impressive part? It has this almost magical ability to soak in the olive oil instead of pushing it away, to absorb it as if it were part of its own flesh.

The reason lies not only in the variety. It’s also the island itself. Schinoussa is low, with earthy hills and fields that slope down to the beaches, with no high mountains to hold the clouds. Rain is scarce, the southerly winds are mild, the soil is poor but naturally well-drained – ideal for a plant that does not love excess moisture.

“The biggest problem is when it doesn’t rain at all. In recent years every winter we’re basically gambling with the weather,” he says, pointing to the reality of climate change.

And yet, despite the harsh climate, the island remains essentially agricultural. Unlike Koufonisia, which turned mainly to fishing and later to tourism, Schinoussa still holds on firmly to farming and livestock as the main occupation of its roughly 150 permanent residents.

Spring, the fields, the fava

That’s why, when you walk in March along the dirt roads that link Chora with Mesaria, you see more fields than houses. The landscape seems to tell you that here, the land is not a backdrop; it’s the protagonist.

If you really want to get to know fava, you don’t come in August. In August, the beaches – Tsigouri, Livadi, Fykio – are the centre of life; the tavernas fill with groups, and fishing boats trace circles around the coves.

You experience it fully in spring. In March and April, if the rains have come, the fields dress themselves in purple blossoms, the plants are at their peak, and people still have the time to sit with you at the edge of the field and tell you their story.

Manolis never tires of talking about the product he reintroduced. Starting from a romantic impulse, he managed to revive the crop and his island, convincing others to invest in a shared vision. “You have to be able to live off the land, not just off the rooms you rent,” he says. “When you have a product of your own place to offer, it gives you an identity. And you also have some money in your pocket from production – you don’t rely only on tourism to survive.”

That’s when it becomes clear that the story of Schinoussa fava is not just another pretty “gastronomic destination” narrative. It is a small but very real act of resistance against convenience: the decision to insist on something so demanding in work, care and weather risk, simply because it is worth it.

Somewhere between spring and summer, on the last Saturday of June, the Fava Festival takes place. The square fills with tables, pots line up in a row and the island dance, the balos, kicks off the celebration early in the evening. People arrive from the neighbouring islands – Naxos, Donousa, Iraklia; some come back from Athens just for this night. It’s the moment when the island collectively remembers that primary production is not just one sector of the economy – it is its very identity.

Taverns and tastes

Whatever time of year you come to Schinoussa, the question is always the same: “Where do we eat the best fava?”

At Bizeli taverna, just outside Chora, fava is served as it should be: warm, velvety, with a little extra olive oil that disappears into the cream before you have time to dip your bread.

At Vrahos, above Tsigouri, the same dish comes with a view over a beach of soft blue water, pale sand and two or three trees casting shade.

Delis, open from late March, welcomes you with plates served right next to locals coming straight from the fields with soil still on their shoes.

And of course there is Kyra Pothiti, in Chora, the place that carries the entire family story of fava: it belonged to Manolis Kovaïos’ mother, and the next generation continues today with recipes that are creative yet deeply rooted in the island’s flavour.

In Schinoussa’s tavernas you’ll try fava “married” with caramelised onions on top, which give sweetness and depth. At the next table they’re serving fava fritters – light, airy, flecked with fennel, throubi and a discreet touch of cumin.

As I leave, I take with me two small bags of fava and a little dust on my shoes. I know that when I open one of those bags at home and let the fava simmer, that bare March field with the purple flowers will come back to me: the sound of the old threshing floor, Manolis’ laughter when he talks about the seed “as if it were his child”.

And just like that, in a deep bowl of golden purée with a drizzle of olive oil on top, Schinoussa will keep revealing itself – every time, from the beginning.